A drug commonly used to treat high blood pressure shows promise in mouse studies for protecting against muscle loss and rebuilding injured muscle. The finding might have implications for slowing the muscle loss that occurs with age and disuse.

We all gradually lose muscle mass and function as we get older. This condition, known as sarcopenia, can pose health risks for older adults. It’s a major contributor to falls and related fractures, and can lead to long periods of hospitalization and rehabilitation. Sarcopenia affects 1 in 4 people under age 70 and about 40% of those 80 and older.

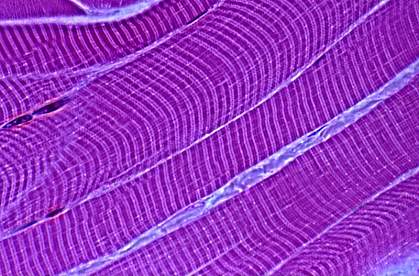

Despite its prevalence, the biological mechanisms underlying sarcopenia are poorly understood. Some studies have suggested a potential role for a protein known as transforming growth factor beta (TGF-β). The activity of this signaling molecule rises in the muscles of older people and leads to a decline in muscle repair. Studies in animals have shown that the activity of TGF-β can be tamped down by the drug losartan, an FDA-approved blood pressure medication. Losartan has been shown to promote regrowth of muscle in mouse models of Marfan syndrome and muscular dystrophy — conditions marked by faulty muscle and connective tissue.

To see if losartan might also affect aging muscle, Dr. Ronald Cohn of the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine and his colleagues studied older mice as they recovered from muscle injury or disuse. Their research was funded in part by NIH’s National Institute on Aging (NIA) and other NIH components. The results were reported in the May 11, 2011, issue of Science Translational Medicine.

In one experiment, 20 mice received losartan in their water for up to 26 days while other mice received placebo. After a week of treatment, the animals’ shin muscles were injected with a muscle-damaging toxin. Four days later, the scientists found no difference in the number of regenerating muscle fibers in the 2 groups. However, after 19 days, the losartan-treated mice had more regenerated muscle and significantly less scar tissue than the untreated animals.

A second experiment looked at losartan’s effects on muscle disuse, believed to be a key contributor to sarcopenia. After a week of receiving losartan-laced water, mice had their right hind shin immobilized by clipping the foot to the leg. The mice could move around freely and were normally active. After 21 days, the mice not treated with losartan had lost 20% of the mass in their immobilized shin muscles. However, the losartan-treated animals lost virtually no muscle mass. The drug seemed to protect against the muscle loss, or atrophy, that occurs with disuse.

“The bigger problem in older people is not muscle injury but muscle disuse. Older adults lose muscle mass and never gain it back,” says Cohn. “As pleased as we were to see that losartan therapy in mice had a positive effect on muscle regeneration, we were most surprised and excited by its striking prevention of disuse atrophy.”

A clinical trial is now being planned to test losartan’s effects on the muscles of older adults.